The stories behind the ‘Windrush scandal’ came to light in the mainstream media in 2018. The Home Office have identified 164 people who had been deported or put in detention since 2002, but the full numbers affected could be thousands. The actions taken by the Home Office that led to several individuals losing their jobs, homes and sense of British nationality, were essentially illegal and have recently been labelled as institutionally racist.

The Windrush Lessons Learned Review, published on the 19 March 2020, into the Windrush scandal suggests that in the Home Office there was an “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race and the history of the Windrush generation”[1].

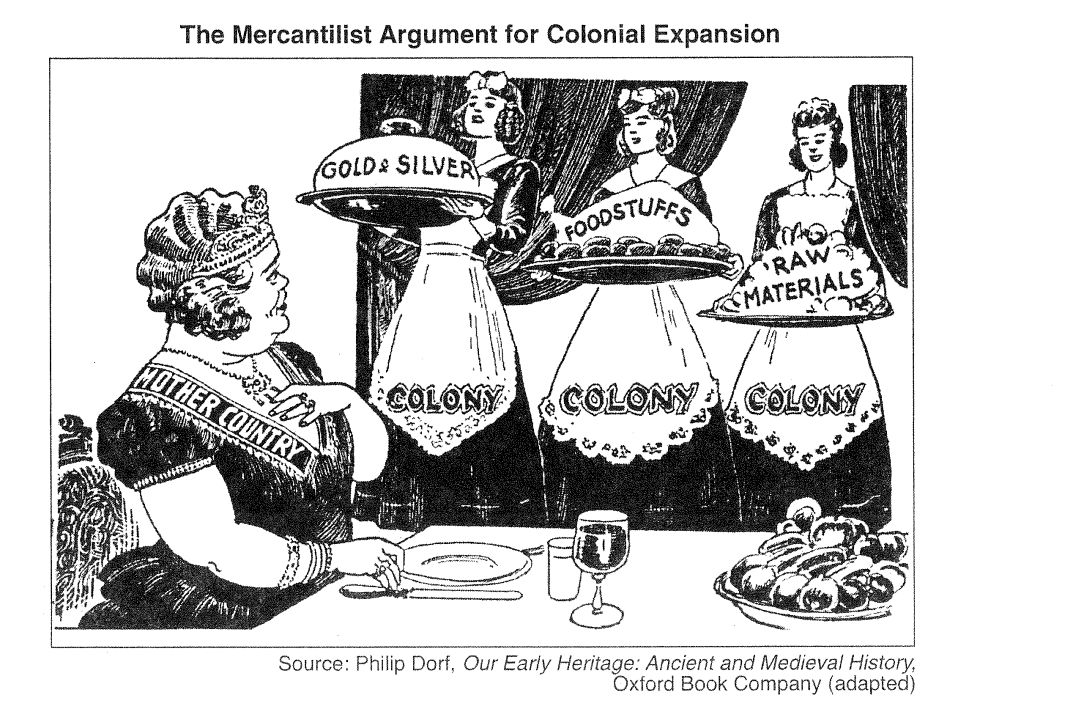

The ‘mother country’

The reason why this group of individuals should never have been treated in this way has been explained by the fact that they had a right to be in the UK. The Immigration Act 1971 gave them the right to live in the UK, but they were not given them any documents to confirm this.

In the corporate world, there is term, ‘corporate knowledge’. A person who has worked for a company for so long that they remember the major projects, restructures, change initiatives, the good leaders and the bad decisions of the past, is said to have corporate knowledge. This person can be the difficult ‘nay-sayer’ when new ideas are floated, but at the same time, they can be a great asset to an organisation, preventing the repetition of ineffective change. Corporate knowledge can also be held in good filing systems and documentation.

For a nation, corporate knowledge is held in its history books, history curricula in education and it is asserted in the way that the media and government communicate what has gone before and what is important now. Which brings me to my point, does anyone remember the ‘mother-country’?

It seems that some people in the UK can reflect on the British empire with nostalgia for a time when the British dominated the world. Often forgetting that domination of the world and the ‘great British Empire’ were built on the enslavement of Africans, and the colonisation of many countries. The Caribbean today is considered by most to be a collection of exotic paradise islands; palm trees, sun, sea and sand – with smiley natives. The only reason that there are black people in the Caribbean at all is due to the European navies enslaving Africans and transporting them there. In the Caribbean now, the languages spoken and the names of towns will tell you which European countries controlled that island at some point. For example, Barbados is the only island that remained in English control for the entire colonial time and therefore has no Spanish or French language or references.

And so, what of the ‘mother country’. The Windrush story starts with the boat that arrives at Tilbury docks in 1948 with the media, government and public response to this. But what about the story from the Caribbean perspective.

“We didn’t see England as a separate entity. For example, in my convent school we spent a lot of time knitting little bits of wool for people during the war, you know, the poor. We didn’t see there was any difference between Grenada and England. “There’ll always be and England and England shall be free” used to be one of our school songs. Empire Day was a big day in Grenada. So it was all part and parcel of what we were about, being part of England.”[2]

This is one story of many. The people in the British colonies in the Caribbean knew nothing other than being part of the empire and looking up to the ‘mother country’. Independence from the UK happened relatively recently from 1962-1983. And this group of immigrants have a particularly unique relationship to Britain. One that almost everyone seems uncomfortable to really address. The complexities of the situation were explained expertly by David Lammy in the speech he made in the House of Commons on the 23 April 2018:

‘The Windrush story does not begin in 1948; the Windrush story begins in the 17th century, when British slave traders stole 12 million Africans from their homes, took them to the Caribbean and sold them into slavery to work on plantations. The wealth of this country was built on the backs of the ancestors of the Windrush generation. We are here today because you were there.

My ancestors were British subjects, but they were not British subjects because they came to Britain. They were British subjects because Britain came to them, took them across the Atlantic, colonised them, sold them into slavery, profited from their labour and made them British subjects. That is why I am here, and it is why the Windrush generation are here.

There is no British history without the history of the empire. As the late, great Stuart Hall put it: “I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea.”’

This is a unique relationship that has never been formally acknowledged, neither has there been an apology, either for what has been taken from Africa, or for the ongoing repercussions on the people who were enslaved and their descendants. Yet, many of their descendants are now in the mother country, and several have been subjected to a hostile and racist environment. Racism defined as less favourable treatment on the basis of race. Race defined legally as colour, nationality, national or ethnic origin.

Tackling inequality at an organisational level

So, what is the answer to this conundrum? What would have stopped this from happening? Quite simple really. People should be competent to do their jobs, and if you work in the Home Office and make decisions about policy then your job competence should include some knowledge of the nationalities that you make decisions about and their relationship to the UK now as you know it and in the past. If structured diversity and inclusion practices were in place in the Home Office this scandal would not have happened.

Diversity and inclusion should not only be seen as a fun and inclusive thing to do, it is fun and inclusive but there is a lot more to it. Instead, see discrimination in an organisation as a disease that has no cure but can be controlled with multiple interventions. In this situation the aims are simply legal compliance and fairness, which has to go beyond a tick box exercise to really shake the core of an organisation, to dismantle the structures that have racism sewn into them.

The fact is that there is incompatibility between the rhetoric of ‘hostile environment’ and the law, which gave this group the right to live in the UK as citizens, and this incompatibility must be confronted. The first step to do this is to agree a definition of what is actually wrong. Bring the history into the board room, let the policy and decision makers discuss British Empire and its impact on current UK societal structures, give them the space to question if those policy decisions are actually legally compliant with the law, or are they based on the politics of today.

Three of the tools in the diversity and inclusion box that would have led to different outcomes:

- Recruitment. If the person specification for policy decision makers stated that they must be knowledgeable in, or able to learn about the relationship of different nationalities to the UK.

- Training. Policy decision-makers in the Home Office should be trained in equalities and human rights legislation. Not just what they are but their complexities with some historical context and discussion of the impact on current society.

- Equality impact assessments. Sometimes called organisational empathy. An organisation takes time to look at the evidence and do effective engagement to analyse if their proposals will have a disproportionately negative impact on diverse groups of people.

But the ground work has to be done. If we aren’t all agreed on what is the issue is then there will be no change. If the leaders don’t fundamentally agree to the report finding that the problem was “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race and the history of the Windrush generation”[3] there can be no effective interventions. For example, if there is generic equality and diversity training without some focus on teaching people about what race is i.e. critical race theory, then the policy makers will not be able to interrogate their actions with some understanding of if their decisions are based on legitimate aims or dangerous rhetoric.

The future of dynamic diversity and inclusion intervention is tackling the issues with a complex awareness of the history of and irrationality of discrimination.

[1] Windrush Lessons Learned Review: Independent review by Wendy Williams; Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 19 March 2020

[2] Phillips, M & Phillips, T; Windrush: The irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain; (Harper Collins, London, 1998) P13.

[3] Windrush Lessons Learned Review: Independent review by Wendy Williams; Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 19 March 2020